A Play of Shadows

The little girl’s eyes widen with amazement as colours create their own moving artwork, mesmerizing in the swiftness with which they paint the screen. Her smaller companions jostle to peek at the sheer energy spilling through the crack in the stretched fabric.

It was a warm summer evening, the skies an odd mixture of threatening pre-monsoon clouds and sunny spells. We had bumped along winding roads passing through red chili fields on one side, water laden canals on the other – cutting through the rice belt of Andhra Pradesh to Narasaraopet, where we hoped to catch a performance of Tholubommallata (literally meaning the dance of leather puppets). The Tholubommallata performers were languidly setting up a little stage at the crossroads: a rickety cubicle of plastic sheets on three sides and one tautly held sheet on the fourth.

An old man with thick ‘soda bottle’ spectacles hobbles over to sit on his haunches on the wet ground. A small crowd mills around and a buzz of village gossip fills the air; not very different from the hum of spectators in the foyer of a theatre show anywhere in the world. The corner shop, in anticipation of a good night of business, stacks up hot chili bhajis, jelebis and bondas. A casual scattering of red plastic chairs and a large loudspeaker blaring tollywood music are the only indications that a performance is about to take place.

An abrupt explosion of cymbals and loud invocations shakes the old man out of his reverie and the gossiping crowd quickly gathers in front of the screen. The story the Tholubommallata perform today is a vignette from the Ramayana – the kidnapping of Sita by the Demon King Ravana, Hanuman’s recce into Lanka and the subsequent fierce battle of victory. The performance begins with an invocation to the gods, and the puppets of Ganesha, Rama, Ravana and Hanuman line up onto the screen.

In the dying light, the colours on the screen turn richer and more vivid, the music taking on a prominence as the rest of the village shuts down. The rhythm of the music draws in a few stragglers, three children crowd into one plastic chair, a toddler settles down into the old man’s lap as both watch mouth agape at the preparations. The sun has set and their faces have a warm afterglow. There is no hard barrier between ‘stage’ and audience, and the children move closer –peeking through the crack in the screen at the performers in the cubicle.

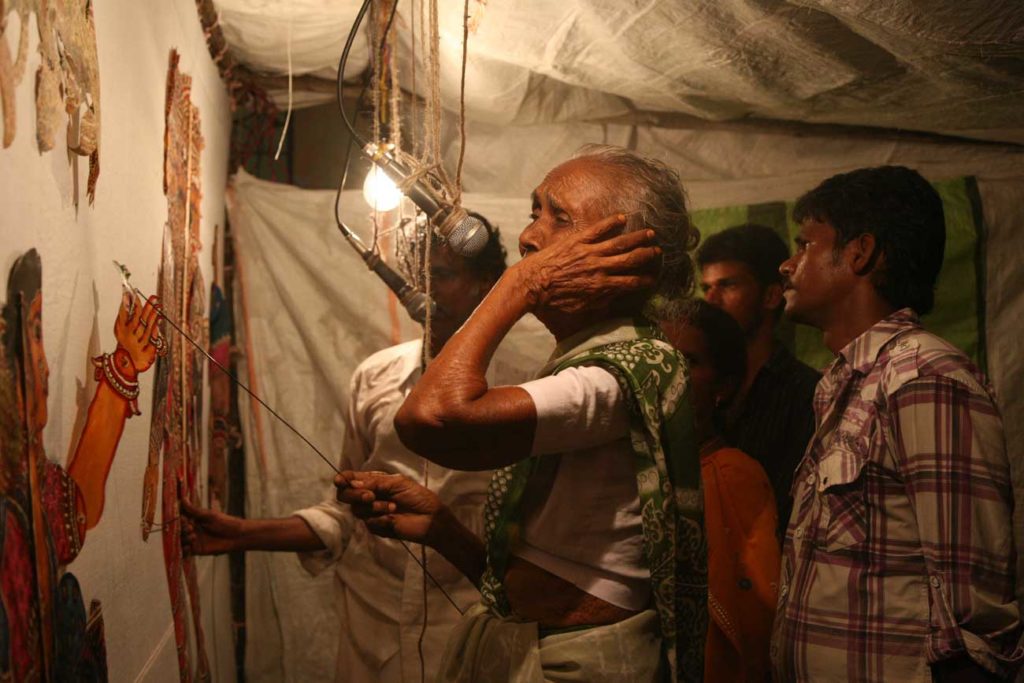

Images on the screen shift swiftly: intricate patterns of ornate garlands and costumes let in gleams of light as phantasmagorical creatures in animated dialogue come in and out. Rama and Laxmana, on the shoulders of the monkey god Hanuman, fly to Vanaras, Hanuman encounters Sampati, the vulture, who gives news of the whereabouts of Sita across the sea in distant Lanka. Sita sits under a marvelously detailed tree; her very stillness emotes despondency as the many-headed Ravana approaches her. Hanuman changes his size: from small and agile, pirouetting on the screen offering hope, he suddenly becomes large and powerful, dominating the arena. Behind the screen, the 70-year old Kottamma has a surprisingly powerful, resonating voice, her hand to her ear as she belts out almost rock star-like. Venkata Dasu, her husband matches the virtuoso singing while he deftly manipulates the rods for the puppets. At times the delicacy and softness of movements is barely noticeable and mirrors the gentility of the dialogue and the music, at others the roars from within the cubicle struggle to keep pace with the fervor of movements that seem to shake the screen dangerously. The village is transported by the grandeur, to another era, another parallel world.

Even though the story has been told innumerable times this rendering is unique to me, I cannot follow the Telugu and barely manage to decipher smatterings of the Sanskrit. However the dramatic turns the story takes are unmistakable, as the fierce battle between the swirling puppets develops – arrows dart across screen, bodies topple and the 30 odd characters enter and leave the screen in operatic style. I wonder at all that fierce energy – concentrated in the tiny cubicle.

Just as one warms to the storytelling, dramatic sound effects change the pace, a jester enters the screen interweaving local jokes into the narrative and the villagers break into laughter. And in one incisive ‘Brechtian’ move the audience is abruptly distanced from the story. This form of folk theatre employs many other ways to deliberately create alienation. Hanuman’s introspective soliloquy forces the spectators to detach from the story and they are provoked into critical reflection. Puppeteers and folk theatre traditionally take the trouble to learn something about their audience; their customs, taboos and current events before a performance. During the performance they speak directly to the audience in a declamatory, rapid and strident manner – doing so they break the ‘fourth wall’, (the term for an imaginary divide between the audience and the performance). By deconstructing boundaries the audience is invited into the narrative – to be part of the shared experience. With no physical division of a stage, spectators surround the performance from three sides and watch the puppets as well as the performers behind the screen. In many ways this puppet theatre and many other folk traditions such as the Chaakyar koothu from Kerala and the Tamasha from Maharashtra employ techniques that remind the spectator of the constructed nature of the theatrical event, thereby keeping the audience at a distance from the narrative at various points in the performance.

The art of puppetry in India is an ancient one and could well have flourished as long as 2000 years ago. Two-dimensional, shadow puppets are illuminated from behind to cast shadows on a cotton screen. The Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka puppets cast colored shadows while those of Orissa and Kerala project black silhouette-like shadows. Tholubommallata from Andhra Pradesh, literally means the dance of leather dolls, Tholu – Leather, Bomma – dolls, Atta – dance. Here a main rod holds the body while two thin rods are attached to the two hands of the puppet for dexterous manipulation. Some characters have two or even three puppets depending on their role in the story, – like Hanuman in this rendering.

Shadow puppet theatre is the forefather of the art of moving images, existing in remote villages much before the advent of the motion picture. Puppet troupes usually consist of members of a family and typically perform at village gatherings, market fairs and school playgrounds. It is magical storytelling – where a handful of performers bring to life a hundred or more colorful mythological characters.

The essence of the Ramayana and other narrative traditions has been expressed across a multitude of cultures and artistic renderings. These diverse and sometimes subversive interpretations ensure that we do not think in the singular. Chimamanda Adichie in her TED Talk says, ‘the danger in the single story’ is that it emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar. The dying of crafts such as the shadow puppets would not merely be a loss of artistic heritage to a nation but would rob future generations of a plurality of thought and expression.

The gift that these performers share goes beyond virtuoso singing, a deft hand with instruments and manipulation of puppets. They each have an ability to form stories in song, to place images clearly in the mind’s eye. Like theatre makers all over the world, folk performers are good at holding onto things that work, but they also know how versatile they must be to survive. However the resilience of these performers is being tested with dwindling patronage and a young generation hesitant to follow family traditions.

The lights dim out and the sleepy grandfather and his even sleepier grandchild retire hand in hand, sucked into the darkness and stillness of the night. The battle is over and good has triumphed. Sita has been rescued and brought back to Ayodhya.

Performance: Sri Venkateswara Leather Puppet Show.

Photographs: Sarita Sundar, Ramu Aravindan

A version of this post was published in The HINDU FRIDAY REVIEW » September 27, 2012

http://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/theatre/art-adroit/article3942139.ece