Distressed Walls and Flânering: The Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2016

This article was first published as ‘Distressed Walls and Flânering: The Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2016’, in Museum Worlds – Berghahn Journals (Volume 5 / 2017) by Sarita Sundar © Berghahn Books doi:10.3167/armw.2017.050119

“A horizontal frame: steps leading down to the canal, grey industrial buildings on the opposite bank. On the extreme left, the roots of a gnarled tree clutch onto a weather-beaten wall. Under the tree stands a man in silhouette. On the right, facing the waterfront is a seated, still figure wrapped in a light pink cotton shroud. A sudden gust of wind whistles through the tableau making the leaves of the tree flutter; the figure pulls the thin cotton wrap tighter and the man, in a policeman’s khaki uniform, steps out from under the tree. He looks like he is going to address the seated figure, a girl, maybe? Mid-step, he hesitates – like he has changed his mind – turns, walks back, leans one leg against the tree and looks out onto the water. But his reverie does not last long as he stands upright and moves once again to the center of the frame…”

I encountered this tableau just as I stepped out from one of the waterfront halls of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2016 (Figure 1). In one of the stark halls was a marble sculpture of a shroud “with an absent seated figure” (Figure 2). This sculpture, by artist Alex Seton called Refuge, depicts emergency blanket-like material used by refugees and “evokes international asylum seeker crisis”(Kochi-Muzris Biennale Catalogue 2017). The catalogue for the Biennale explains that the stark, cold hardness of the marble and the bodiless figure symbolize the impersonal, authoritarian attitudes that refugees often face in detention centers (KMB Catalogue 2017).

Figure 1: The tableau at the waterfront at Fort Kochi. (Sarita Sundar 2017)

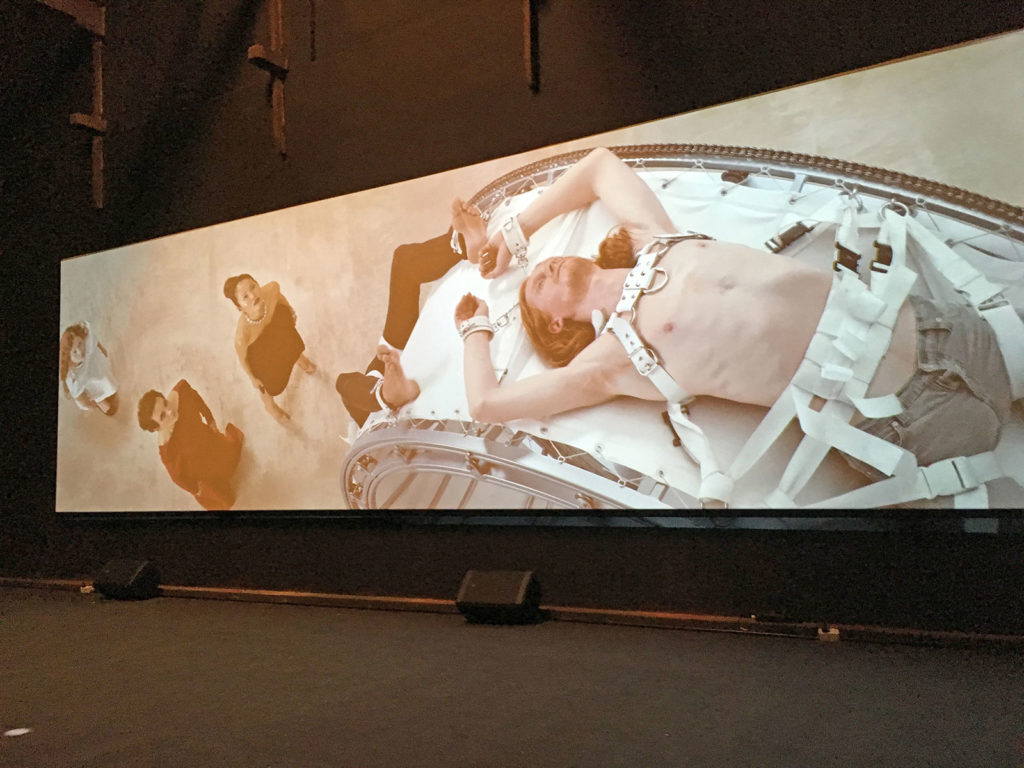

In a nearby hall, a 25-foot video installation called Inverso Mundus, or Reverse Worlds, by artists AES+F, depicts a series of confrontations between corseted bodies and impassionate observers in a topsy-turvy gender-ambiguous world. The orchestrated figures move across the screen in swirling trajectories that blend and fuse into one another (Figure 3). These installations are decidedly surreal, and yet beg the question of whether we can truly differentiate when traversing ‘grounded reality’ and the hyperreal worlds of created spectacles – digital or physical.

Figure 2: Refuge by Alex Seton at Kochi-Muzris Biennale. (Sarita Sundar 2017)

Figure 3: Inverso Mundus by AES+F at Kochi-Muzris Biennale. (Sarita Sundar 2017)

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB), located in the port city of Kochi in the south Indian state of Kerala, concluded its four-month long third edition in March 2017. While there is an inherent site specificity to the event, themes displayed in the Biennale address issues and audiences far beyond the city. An initiative of the Kochi Biennale Foundation with support from the State Government of Kerala, the KMB also has support from corporates, artists, art councils, embassies and individuals from the community who have “walked along during the execution of the project” (Komu, cited in Nair 2014: 43). The Kochi Biennale Foundation (KBF) is a non-profit charitable trust engaged in promoting art- and culture-related educational activities, and also in the conservation of the tangible and intangible heritage of the region.

Kochi is closely linked to the maritime period of the ‘Age of Discovery’, when a stream of navigators arrived on the Malabar coast in south-west India after crossing vast, uncharted seas in search of ‘such treasure and rich merchandize’ (Coke Burnell 1885). Muziris was a thriving multi-cultural port and a confluence of many religions till a flood in the 13th century destroyed it – losing its significance in world trade to Fort Kochi soon thereafter. Muziris, or Pattanam as it is called today, is a protected heritage and archaeological site 50 kilometres north of Kochi. Material evidence of trade and travel going back to the 1 st century BC can be found in the Muziris Children’s Museum that is situated within the archaeological site compound. The hyphenated name of the KMB is a conceptual link to the archaeological excavation at Muziris which has revealed many complex layers of contestations – of history, identity, culture, place, economics, and politics. This conceptual connection views the Biennale ‘site’ as a place of continuous discovery – a place of digging, learning and uncovering layers – core to the ethos that the founders, Riyas Komu and Bose Krishnamachari, have strived to achieve across all editions of the Biennale (Komu 2017).

“Kochi’s cosmopolitanism is one that has been worn by generations in Kerala as a badge of honour even as it has led to a series of struggles…” (Krishnamachari and Komu 2012). Autorickshaw drivers doubling up as Biennale tour guides point out exhibition halls, mosques, churches and temples all within walking distance from each other; while local artists document and celebrate the plurality of traditions and communities of the area. Sudarshan Shetty, curator of the 2016 edition, explains the title, Forming in the Pupil of an Eye, with an anecdote of a sage who opens his eyes onto the world, embracing its multiplicity and then reflecting back all that the eyes take in. This ethos is what the Biennale attempts – to render multiple realities that are often unclear and hidden; and to foster opportunities to be simultaneously reflective and reflexive. Within the Biennale halls, when audiences encounter novel ideas, texts or cultures they are prompted – often provoked – to examine claims and assumptions; to carefully consider, meditate and then look within themselves for further meaning and respond individually and hence uniquely.

In today’s ‘societies of the spectacle’, many cultural escapades – such as biennales and literature festivals – encourage the participation of the audiences. And, as I stepped out from the intensely charged air of the stark gallery halls – I was pliant participant in making spectacles ‘happen’ – only too ready to inhabit the illusions I had created. The walls of the Biennale halls, with their casually distressed finishes are quite unlike the forbidding, white and aloof walls you might find in most modern art galleries. Here, there are hardly any barriers as the natural patina of decaying walls found in many of the buildings of the Kochi Fort seep into the curated spaces. It was easy enough for me to imagine that the tableau I witnessed at the waterfront was ‘performance art’. The innocent, if serendipitous, coming together of a uniformed person of authority and a shrouded, crouched figure within that visualized stage was up for display; the imagined tensions and confrontations between the actors at the waterfront were to be studied with as much reverence as the installations within the curated halls.

As the city and the KMB galleries osmose into each other the question arises: Where does real life end and where does simulation begin? People, objects and beings seem to bleed and liquefy into one another within the hyperreality of the city-biennale. Along the waterfront, the Chinese fishing nets do a rhythmic up and down dance – a performance – watched closely by fishermen and casual passersby. After the early morning catch, fish arranged on plastic sheets – becomes hurriedly fashioned sales displays but also harmoniously crafted canvases of independent expression (Figure 3). And, at the roadside hawker, as my companion and I sip tea, we suddenly realize we are the actors, the ‘oddities’ for the ‘regulars’. We are the ‘curiosities’ that need to be observed, questioned and studied. The whole city of Kochi for the 108-odd days of the event becomes a seamless museum with objects waiting to be labelled and interpreted – even if only in stealth.

Figure 4: The early morning’s catch on display at Fort Kochi. (Sarita Sundar 2017)

Chris Dercon, former director of Tate Modern called the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2014 “a blueprint for museums of the future”. He envisaged that future museums will not be housed in vast buildings but instead will consist of “simple, humble and flexible structures in many small spaces” (Dercon 2014). The KMB in the fort city of Kochi, contained and in some ways even constrained within a dense network of waterways, remains successfully independent – located at a distance from and on the periphery of the more well known and forceful metropolitan centers of art in India. This isolation seems ideally suited to serve as a laboratory for tomorrow’s museums. What it lacks in infrastructure and monumentality, the site of the Biennale gains in being located within a historically rich, culturally diverse, highly literate and vibrant – if occasionally polemic society. In a region that has historically embraced the global contemporary, the activities and ethos of the Kochi Biennale Foundation reverberate beyond just the months allocated for the Biennale and the city-biennale quite easily becomes a city-museum.

Discussions on the ‘biennale phenomenon’ worldwide have explored the artistic, theoretical, political, and other ambitions of large-scale exhibitions from the first Venice Biennale in 1895 – that started from conservative displays of art to proto-nationalist spectacles – to the present day avant-garde international extravaganzas. Specifically, art critics have discussed how the KMB has corporatized and commodified art and transformed the tourism industry and the landscape of Kochi (Kapur and Ginwala 2017). The “biennale effect” (D’Souza and Manghani 2017) is seen as a broader critical framework for understanding the context and sites of the art on display and its effects within the art and cultural world. But the question remains to be asked: has the Biennale transformed visitors? If so, how has it changed the way audiences see?

John Berger asserts that ways of seeing are influenced by how images are created as well as how they are read:

“The photographer’s way of seeing is reflected in his choice of subject. The painter’s way of seeing is reconstituted by the marks he makes on the canvas or paper. Yet, although every image embodies a way of seeing, our perception or appreciation of an image depends also upon our own way of seeing (Berger 1972).”

Are visitors establishing their place in the surrounding world in the way they see? Do cultural escapades to grand spectacles, like the Biennale, transform visitors by making them producers and actors in their own performances, the destinations part of their own narrative, and everything they see as central and significant? As the whole city becomes a museum, ubiquitous objects and casual occurrences, whether carefully curated or unexpectedly found, become museum objects, performance art or installations – to be examined with care and precision.

While cultural escapades surely encourage different ways of seeing and then interpreting, the other thing that the Biennale and such events offer is an opportunity to dissociate from daily surroundings, of taking a step back, to become flâneurs for a brief moment, or if one is privileged with time – for a few days. The academic community, and in particular Walter Benjamin, has used the flâneur to explain the modern, urban condition, to explain class tensions and gender divisions (Lauster 2007). ‘Flâneur’ conjures images of Parisians strolling along boulevards as they debate the latest ‘isms’ – the newest movements in art or philosophy. Notwithstanding that most of us are neither Parisian nor academic, doesn’t flânerie have the potential today to become a pastime – a skill needing careful cultivation. As visitors step out of the curated halls in Kochi, have their ‘ways of seeing’ become finely honed to examine small town life, alienation, class tensions, and the like? As we grow inescapably busier – and we feel the need to respond immediately to every message sent to our technology-strapped bodies – might the relaxed and laid-back art of flânerie be due for a revival?

Every experience on the ambulatory strolls within the curated halls has the potential to lead onto pleasantly accidental encounters – such as the tableau I witnessed on the waterfront. However, before committing to flânering, it may be important to refine certain skills or even unlearn a few others. The need to tick off locations on ‘designer’ maps must be resisted; proffered advice from well-meaning friends on must-do agendas must be resolutely ignored. It may be more important for successful flânering to wander a bit aimlessly from one site to the next; to amicably accept that the pursuit of one thing may lead to the discovery of another; to be ready to amble and seek out that tantalizing ‘something’ peeking from around the corner – even if it is not labelled on well-intentioned event maps.

There are many things in common with cultural events (like literature and music festivals) held in small towns in India that encourage new ways of seeing and the pursuit of flânering. Undependable data connectivity in small towns mean there are no insistent ‘pings’ to respond to. Friendly streets provide enough distraction and safe flânering for diverse groups. Aesthetically designed cafés serve espressos in little cups for middle-aged foreigners; boutique shops sell touristy knickknacks for mothers and daughters on girlie trips; kitschy popular culture on roadside walls excite packs of designers and artists; watering holes off the beaten track offer local cuisine for adventurous foodies. But the one possible difference between the Kochi-Muziris Biennale and cultural escapades in other cities is the way in which the event embraced the citizens of Kochi and vice versa.

Kochi is a melting pot of cultures where communities over the centuries have come to find refuge, trade, develop roots and eventually integrate into local society. Today the Biennale has brought together a multiplicity of viewpoints and representations embraced not just by the national and international art world but also the citizens of Kochi and around. And even if the first edition of the Biennale had teething problems, over the last few editions of KMB, as Chris Dercon says, “grumble has given way to wonder among viewers and a sense of participation”(Dercon, cited in Priyadarshini S. 2014). In the 2016 edition, the decaying halls, not at all distant and aloof, were full of local school children, women in office groups, families with grandparents in tow – all of them participating as visitors, audiences, actors and performers – all hopefully awakened to a new way of seeing and

flânering.

Fostering serendipitous experiences and forging personal narratives on the fringes of formally curated events are among the many opportunities afforded by events such as the Biennale. As I continued to stalk another khaki-clad policeman with my phone camera, my travelling companion asks, “Is this a thing for you now?”

Thank you Shobha for the mindful editing and the companionship!

Reference List:

- Berger, John. 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books and British Broadcasting Corporation.

- Coke Burnell, Arthur. 1885. The Voyage of John Huyghen Van Linschoten to the East Indies: From the Old English Translation of 1598. Volume 1. London: The Haklyut Society.

- Dercon, Chris. 2014. “Kochi-Muziris Biennale is a Blueprint for the Museums of the Future”. Kochi-Muziris Biennale Website. http://kochimuzirisbiennale.org/chris-dercon-kochi-muziris-biennale-is-a-blueprint-for-the-museums-of-the-future/

- E. D’Souza, Robert and Sunil Manghani, eds. 2017. India’s Biennale Effect: A Politics of Contemporary. New York: Routeledge.

- Kapur, Geeta. 2017. “Kochi-Muziris Biennale and the Biennale Phenomenon. Marg. 68 (2): 37-44 Komu, Riyas and Krishnamachari Bose. 2012. “Concept”. Kochi-Muziris Biennale Website. http://kochimuzirisbiennale.org/concept/

- Komu, Riyas. 2017. “ Muzris and the Many Pasts of Kochi”. Marg. 68 (2): 22-29.

- Lauster, Martina. 2007. “Walter Benjamin’s Myth of the Flâneur”. The Modern Language Review. 102 (1): 139-156.

- Nair, Manoj. 2014. “Three is Company”. Arts Illustrated. Dec 2014: 42-52. artsillustrated.in/kochi/my-product/three-is-company/

- Shetty, Sudarshan. 2016. “Curatorial Note”. Kochi-Muziris Biennale Website. https://www.kochimuzirisbiennale.org/kmb2012-curatorial-note/

- S. Priyadarshini. 2014. “Roots in the Past, Shoots to the Future”. The Hindu. December 19 th 2014.